illions of years ago a vent tore open fifty miles beneath what is now central Arizona. Through this lesion the pressures of the deep interior took slow aim at the roof of that world, the floor of our own, and commenced a bombardment of molten rock that is continuing still. Over time this barrage, the remains of which are known as the San Francisco Volcanic Field, walked north and east, just nicking the edge of the Painted Desert, near what are now Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico. Right at the point where field and sands touch, a small, exceptionally well formed cinder cone can be seen, standing off from the other volcanoes, deeper into the desert. From a certain angle the cone has the shape of a bow wave, as though something alive were running under the sand, out toward the midst of the coral and orange landscape. This is Roden Crater.

illions of years ago a vent tore open fifty miles beneath what is now central Arizona. Through this lesion the pressures of the deep interior took slow aim at the roof of that world, the floor of our own, and commenced a bombardment of molten rock that is continuing still. Over time this barrage, the remains of which are known as the San Francisco Volcanic Field, walked north and east, just nicking the edge of the Painted Desert, near what are now Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico. Right at the point where field and sands touch, a small, exceptionally well formed cinder cone can be seen, standing off from the other volcanoes, deeper into the desert. From a certain angle the cone has the shape of a bow wave, as though something alive were running under the sand, out toward the midst of the coral and orange landscape. This is Roden Crater.

In the past few years a swelling stream of curators, astronomers and other scientists, artists, journalists, and collectors have been flying into Flagstaff to visit a construction project nearby. The exact nature of the project is not simple to pin down, though certainly most visitors would agree that what is proceeding is the construction of a piece of contemporary art—a combination of earthwork, sculpture, and architecture, perhaps, and almost certainly the largest piece of serious art under way in the world today. The Los Angeles Times called it “an astonishing project of staggering magnitude.” An article in The Wall Street Journal said that in Roden Crater “the sun and the moon and the stars will be given the stage upon which they [will] have the opportunity to present themselves as they will, like dancers in the sky.” John Russell, of the New York Times, predicted that the crater will “mediate on our behalf between geological time and celestial time. Count Giuseppe Panza di Biumo, a widely respected collector of contemporary art, has called Roden “the Sistine Chapel of America.” A journalist dropped by investigating rumors that the Defense Department had plans for the site.

The view from the lip was remarkable. The summer rains had just fallen, brushing tints of green and flax over the rust and black and tan of the sands outside the cone. Off into the desert, which lay open to view for more than a hundred miles, the land shifted between pinks and oranges as intense as those of cheap cosmetics. None of these hues was stable: as clouds passed and the sun wheeled overhead, the colors of the landscape transformed in measured and deliberate steps, as though a composition were being played. The horizon was punctuated by cinder cones and volcanic buttes, which looked like the cooling towers of thermal power plants. Some rose from the direction of Colorado, some from Utah. Other than Turrell and two visitors from the staff of the Phoenix Art Museum, who sat, legs drawn up, on the opposite rim, there was hardly a sign of the human race. The volumes reaching behind them were so immense that they looked like giants, men carved out of mountains.

Behind and all around the three, dozens of slanted, ribbon-like shadows cast by clouds sailed at different speeds and in different directions. There was a sense of standing on the floor of an ocean saturated with light. In between the desert and the surface of this ocean, miles overhead, lived the gliding shafts of cloud shadow, the sheets of air, each marked with a distinct species of cloud, crossing each other at different altitudes, and the patterns of radiance shifting as the sun, curving west, picked out and illuminated the texture of the atmosphere, as if with pedagogical intent. A smooth, gustless cool dry wind, the motor of the tumbleweeds, streamed up the sides of the volcano and poured into the sky.

After several minutes Roden, which is seventy-five stories above the desert floor, seemed to flatten right out onto the desert floor. All that was left was an acre of tumbleweed, lying flat as a stain. The great weight of the space above appeared to press the crater down into the desert like a preserved leaf. Later I mentioned this illusion to Turrell. “Right,” he said, as though I had answered a question.

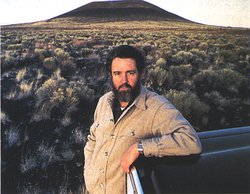

he reasons visitors arrive, contribute, and go home with enthusiasm probably lie less in the view than in the reputation of the artist behind the project. Though only in his mid-forties, James Turrell is by any standard a major American artist. He has had retrospectives at the Whitney Museum of American Art, in New York, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, in Los Angeles, and he has shown at the Leo Castelli Gallery, in New York, one of the more prestigious private galleries in the world. He holds a MacArthur fellowship.

he reasons visitors arrive, contribute, and go home with enthusiasm probably lie less in the view than in the reputation of the artist behind the project. Though only in his mid-forties, James Turrell is by any standard a major American artist. He has had retrospectives at the Whitney Museum of American Art, in New York, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, in Los Angeles, and he has shown at the Leo Castelli Gallery, in New York, one of the more prestigious private galleries in the world. He holds a MacArthur fellowship.

These triumphs have rested on his mastery not of oil or watercolor but of a medium known as the “homogeneous field,” a visual experience that is to the eye what white noise is to the ear a perfectly featureless sensorium. The reader might experience one of these fields by cutting a hole in a large piece of paper, taking it outside, and holding it in front of a region of the sky that is cloudless, not uncomfortably bright, and above the building line. The area within the hole is a homogeneous field. (The sky is usually too bright to allow prolonged investigation of homogeneous fields by this means, however.) Perhaps the best known of these “undifferentiated surrounds” are whiteouts - the moments during snowstorms when every line, shade, shape, and form is swallowed by an encompassing whiteness.

Until Turrell grasped their expressive power, these fields had been curiosities of the psychology lab. They were studied first by gestalt psychologists in the thirties, who surrounded subjects with meticulously whitewashed and neutrally lit boards in the hope that “homogeneous stimulation” of the visual field, or the Ganzfeld, would reveal the nature of the primal visual experience. The technique was reborn in the early fifties, when perceptual psychologists developed several new ways of generating the fields. One was to split a Ping-Pong ball, tape the hemispheres over the eyes of the subject, and project lights, which might differ in color between the right and the left, onto the curves of the ball halves.

Both generations of psychologists found the technique difficult to control: their subjects couldn’t agree on what it was they were seeing. Apparently, the human retina refuses to believe in homogeneous fields. When exposed to one, it tolerates the phenomenon for a few moments and then begins casting about for other possibilities. Different retinas produce different theories. The most common report was of “swimming in a mist of light which becomes more condensed at an indefinite distance.” Most subjects described “sensing something vaguely surface-like in front of the face” some described a “cone-shaped three-dimensional surface,” a “cracked-ice effect,” a “web-like structure,” or rings of different sizes and shapes. There were reports of memory activation, time distortion, and other hallucinations. Sometimes observers felt that their eyes were in violent motion. When a homogeneous field was used as the ground against which an object was viewed, contours blurred and shapes transformed. Sometimes the objects seemed to vanish, leaving subjects uncertain as to whether their eyes were even open. After effects included extreme fatigue, great lightness of body, dizziness, and impaired motor coordination, sense of balance, and time perception. Sometimes subjects appeared intoxicated.

Both generations of psychologists found the technique difficult to control: their subjects couldn’t agree on what it was they were seeing. Apparently, the human retina refuses to believe in homogeneous fields. When exposed to one, it tolerates the phenomenon for a few moments and then begins casting about for other possibilities. Different retinas produce different theories. The most common report was of “swimming in a mist of light which becomes more condensed at an indefinite distance.” Most subjects described “sensing something vaguely surface-like in front of the face” some described a “cone-shaped three-dimensional surface,” a “cracked-ice effect,” a “web-like structure,” or rings of different sizes and shapes. There were reports of memory activation, time distortion, and other hallucinations. Sometimes observers felt that their eyes were in violent motion. When a homogeneous field was used as the ground against which an object was viewed, contours blurred and shapes transformed. Sometimes the objects seemed to vanish, leaving subjects uncertain as to whether their eyes were even open. After effects included extreme fatigue, great lightness of body, dizziness, and impaired motor coordination, sense of balance, and time perception. Sometimes subjects appeared intoxicated.

Viewer reaction was hard to control and categorize, and perhaps for this reason homogeneous, fields soon disappeared, from serious scientific literature. However, they, had not quite done so by the early sixties, when Turrell, then a student at Pomona College, ran across references to them while pursuing an interest in the perception of light.

During that decade the art culture of the nation was, naturally, radicalized. One form this took was a systematic hostility to art as a commodity—as something that could be marketed, bought, auctioned off, or collected. Performance art and earthworks were part of this critique. A third and less well known part was “perceptual environments,” which set out to suggest that the perception of an object was less a function of the object itself than of the establishment-defined environment surrounding that object. This was the wing Turrell drifted into and the context in which he began to explore the special power of the homogeneous field. In particular, in 1968 Turrell, the Los Angeles artist Robert Irwin, and Ed Wortz, a physiological psychologist, entered into a celebrated collaboration to probe the possibilities of the fields.

During that decade the art culture of the nation was, naturally, radicalized. One form this took was a systematic hostility to art as a commodity—as something that could be marketed, bought, auctioned off, or collected. Performance art and earthworks were part of this critique. A third and less well known part was “perceptual environments,” which set out to suggest that the perception of an object was less a function of the object itself than of the establishment-defined environment surrounding that object. This was the wing Turrell drifted into and the context in which he began to explore the special power of the homogeneous field. In particular, in 1968 Turrell, the Los Angeles artist Robert Irwin, and Ed Wortz, a physiological psychologist, entered into a celebrated collaboration to probe the possibilities of the fields.

During the next ten years Turrell discovered how to create these “light mists,” as some call them, so that they could be experienced by wandering spectators—people who were not even seated, let alone wearing Ping-Pong balls. He would, for example, paint a chamber with titanium white, manipulating its dimensions and illumination until someone looking into the enclosure saw the desired effect. He learned how to make his chambers responsive to external events such as the presence and the pace of spectators; how to work with different qualities and intensities of light (he continues to use every kind of source, from argon, quartz halogen, xenon, and tungsten bulbs to fluorescent tubes and simple daylight, moonlight, and starlight); how to introduce structures, like screens of light, into the fields; how to tint the fields with different hues, and how to make them seem to shimmer, to fill up with smoke, to develop a grain, to present a skin or surface. During this time he exhibited only twice, once in Holland and once in Los Angeles. (Turrell also restores antique airplanes, a lucrative sideline that has made him financially independent of the exhibition, grant, and academic-appointment games.) When his show opened at the Whitney, in 1980, almost no one in the New York art world had any advance word on him.

A visitor to the show saw chambers, most the size of small rooms, filled with light.

There was nothing in these spaces but light, usually of a single shade. There was almost no sense of the artist’s hand, of a deliberate manipulation. The light in the chambers appeared alternately transparent and opaque. Some viewers experienced an illusion of solidity so pronounced that they tried to lean against the large chamber openings and fell through; three of them suffered such injuries to their bodies and egos that they filed suits against Turrell for maintaining a deliberate and dangerous deception. The critics were ecstatic. They declared the medium sensationally novel and the pieces utter knockouts, combining sensuousness with minimalist elegance. Many found them numinous, mystical, an invitation to meditate on the nature of the void. In particular, the critics embraced the very feature that had made the Ganzfeld seem so appropriate as a critique of the art experience - their power to destabilize perception, the delicious way in which they subverted the very idea of looking. Ross Wetzsteon, of the Village Voice, wrote,

There was nothing in these spaces but light, usually of a single shade. There was almost no sense of the artist’s hand, of a deliberate manipulation. The light in the chambers appeared alternately transparent and opaque. Some viewers experienced an illusion of solidity so pronounced that they tried to lean against the large chamber openings and fell through; three of them suffered such injuries to their bodies and egos that they filed suits against Turrell for maintaining a deliberate and dangerous deception. The critics were ecstatic. They declared the medium sensationally novel and the pieces utter knockouts, combining sensuousness with minimalist elegance. Many found them numinous, mystical, an invitation to meditate on the nature of the void. In particular, the critics embraced the very feature that had made the Ganzfeld seem so appropriate as a critique of the art experience - their power to destabilize perception, the delicious way in which they subverted the very idea of looking. Ross Wetzsteon, of the Village Voice, wrote,

As you watch, your sense of substance constantly shifts—the panel solid, then dematerialized, then solid once more . . . the panel floats in space, toward you, away from you, shimmering in place. You’re hypnotized, confused—what you experience contradicts what you “know,” and you begin to realize that James Turrell’s work is asking you to question the very nature of materiality.

A “brilliant success,” said Robert Hughes, of Time.

In contemplating these peaceful and august light chambers, one is confronted ...with the reflection of one’s own mind creating its illusions and orientations, and this becomes the ‘subject’ of the work. The art it transpires, is not in front of your eyes. It is behind them.

person thinking about homogeneous fields would naturally find himself reflecting on the greatest of these: the sky. Turrell, an enthusiastic pilot who spends as much time in the air as he can, had abundant opportunity for this sort of reflection, and in

person thinking about homogeneous fields would naturally find himself reflecting on the greatest of these: the sky. Turrell, an enthusiastic pilot who spends as much time in the air as he can, had abundant opportunity for this sort of reflection, and in  the early seventies found himself focusing on the sky’s height. The illusion that the sky is a ceiling, which goes by the pretty name of celestial vaulting, is famously strong in children, and most of us, if asked to set aside what we know about the atmosphere, could come up with an altitude at which the ceiling appears to lie at any one moment. This figure is not stable. The apparent height of the sky is a function of the apparent distance of the horizon: specifically, the closer the horizon, the lower the ceiling. (It seems that our sense of the sky’s form stays the same regardless of the altitudes we are at.) Turrell’s first thought was of a big bowl in which people could walk up and down, the interior walls. As, viewers moved down the, sides of the bowl, the horizon, defined by the lip, would narrow and the sky would descend. What he found most intriguing about the idea, he says, was its power to demonstrate that people

"control the shape of the space in which they move."

the early seventies found himself focusing on the sky’s height. The illusion that the sky is a ceiling, which goes by the pretty name of celestial vaulting, is famously strong in children, and most of us, if asked to set aside what we know about the atmosphere, could come up with an altitude at which the ceiling appears to lie at any one moment. This figure is not stable. The apparent height of the sky is a function of the apparent distance of the horizon: specifically, the closer the horizon, the lower the ceiling. (It seems that our sense of the sky’s form stays the same regardless of the altitudes we are at.) Turrell’s first thought was of a big bowl in which people could walk up and down, the interior walls. As, viewers moved down the, sides of the bowl, the horizon, defined by the lip, would narrow and the sky would descend. What he found most intriguing about the idea, he says, was its power to demonstrate that people

"control the shape of the space in which they move."

For anyone else with these interests, the next step would have been to apply for

a grant to build a huge wolf on some municipal plaza. Turrell instead made a

remarkable decision: only a volcano crater would do. And not just any crater. It

should have a rim that was both circular and flat (qualities that would simplify

the construction and intensify the experience of celestial vaulting), be 400 or

500 feet above the plain and at least 5,000 feet above sea level (so that the

sky’s color would have begun to deepen), he away from the light pollution and

haze of a city, and be in a setting that would extend the artwork into the

surrounding landscapes and skies “so that the piece itself would have no end.”

After working out the specs, Turrell got in his plane and flew off to inspect,

individually, each of the thousands of volcanoes dotting the North American

cordillera, the complex of ranges that twists up and down the West. The search

took seven months and more than 500 hours of air time, and extended from the

Canadian border to the Mexican border. Eventually he worked his way to the San

Francisco Volcanic Field and found Roden.

Roden fell short of perfection in only one respect: its dish was not circular but

saddle–shaped. Otherwise, it had everything, including the advantage of being

privately owned and therefore free of the public-lands bureaucracy, which Turrell

thought might prove slow to appreciate his intensions.

As it turned out, he had

the same problem with the actual owner, a cattle rancher, who could not be

persuaded of the benefit of having an art museum, or something, right in the

center of his range. Turrell put him on hold for a bit and approached the Dia Art

Foundation, which specialized in supporting large environmental pieces. Dia

agreed to buy the crater, pay for reshaping the bowl, and take over

responsibility for maintenance and visitor control once the project was finished.

Turrell went back to the owner, who once again refused to sell.

Roden fell short of perfection in only one respect: its dish was not circular but

saddle–shaped. Otherwise, it had everything, including the advantage of being

privately owned and therefore free of the public-lands bureaucracy, which Turrell

thought might prove slow to appreciate his intensions.

As it turned out, he had

the same problem with the actual owner, a cattle rancher, who could not be

persuaded of the benefit of having an art museum, or something, right in the

center of his range. Turrell put him on hold for a bit and approached the Dia Art

Foundation, which specialized in supporting large environmental pieces. Dia

agreed to buy the crater, pay for reshaping the bowl, and take over

responsibility for maintenance and visitor control once the project was finished.

Turrell went back to the owner, who once again refused to sell.

Turrell simply kept asking. During these discussions, which went on for three

years, he visited the crater often. He slept in it, winter and summer, and

noticed how the volcano aligned itself to the dawn and the sunset, to the

ecliptic, and to the orbits of the planets, and how the colors of the site, of

land and sky, changed with the seasons. One day, when he was wandering around

outside the crater, Turrell looked up and noticed that a cap cloud had formed

over the top of Roden. He scrambled up the side of the volcano as fast as he

could and plunged into the cloud. It was different from thick seacoast fogs, in

which the light level is quite low, he says. At this altitude, nearly 6,000 feet above sea level, sunlight penetrated all through, evenly lighting the suspended droplets. The whole space glowed: a homogeneous field.

urrell asserts that no one flying overhead will have any sense that construction has taken place. He intends to replant the bowl with the original vegetation, which will come as a shock to the tumbleweeds. The finished project will have none of the clues that identify works of art or art institutions: there will be no labels on the walls, no information booth, no recorded cassette lectures for rent. There will be no gift shop, restaurant, visitors’ register, or plastic box for contributions. No postcards will be sold. There will be no security guards, parking lot, landing strip, or escalators. In fact, if Turrell’s dream is perfectly realized, there will be no spectators, or hardly any: he thinks the largest number of visitors the project can handle will be around three a day.

urrell asserts that no one flying overhead will have any sense that construction has taken place. He intends to replant the bowl with the original vegetation, which will come as a shock to the tumbleweeds. The finished project will have none of the clues that identify works of art or art institutions: there will be no labels on the walls, no information booth, no recorded cassette lectures for rent. There will be no gift shop, restaurant, visitors’ register, or plastic box for contributions. No postcards will be sold. There will be no security guards, parking lot, landing strip, or escalators. In fact, if Turrell’s dream is perfectly realized, there will be no spectators, or hardly any: he thinks the largest number of visitors the project can handle will be around three a day.

Roden will be swept clean of references not only to the artist, art object, and art institution but also, aside from a few concessions to safety, to post-Renaissance Western civilization. There are no lenses at Roden, no track lighting, no loudspeakers. (The “radio room” is one example of the ingenuity with which references to this civilization have been dodged. ) Someone left to poke around the project on his own, knowing nothing of the actual history, might guess that it was a temple built thousands of years ago by a sect of Native American sky-worshipers and long since abandoned. As much as possible, only local minerals are being used: desert sand, volcanic obsidian for the resonating bathtub, and shale from the bottom of a nearby Jurassic lagoon for the outside walkways, which will give the construction the look of having been built by a people without trucks. (One chamber escapes from the present era in the other direction: a shaft pointed to the North Star is intended to monitor the precession of the earth’s pole from Polaris to Vega, which will become the new North Star in 12,000 years.)

Yet the enterprise could not be more high-tech. For instance, the astronomer collaborating with Turrell on the moon-sighting tunnel, Dick Walker, of the naval observatory at Flagstaff, has been working on the math for three years. Drilling the tunnel will require a laser-guided “mole."

If Turrell could remove all traces of human association, so that Roden looked as though the earth itself had carved it, I have no doubt he would do so. He plans to lay down his local materials oldest first, as if Roden had been built up by geological forces. Something like this must have been in his mind fifteen years ago, when he decided that his celestial-vaulting piece had to go into a crater or nowhere, at a site where the piece would have no end. This instinct for distancing himself from what he does is constantly apparent. Once, Turrell took me flying over the desert. After we had woven this way and that, he nosed toward a notch in a range of nearby hills. “Hogan down there,” he said, pointing with the tip of his beard to a circular Navajo dwelling. Obediently I looked down. Sure enough, a hogan. Not that rare a sight in Arizona, but still... I looked up just as he nudged the Heliocourier through the notch and the Grand Canyon exploded around me. I leapt up; the seat belt jerked me back. Turrell stared innocently ahead, as if to say, Who, me? Hey, I just fly this thing.

s oblique as Turrell can be, after hanging around for a few days I did begin to get a sense of a metaphysic. He seems to have a vision of a world whose active components are not physical entities, things with weight, but spaces. To most of us, a visual act or event is a two-party affair, linking the observer with the observed. Turrell seems to believe that all the action happens in the space that separates the two. The space makes all the decisions; it controls what the observer gets to see and what the observed gets to show. Sometimes it seems that he sees spaces as conscious life forms; he talks of watching spaces watch themselves. “Roden Crater has knowledge in it, and it does something with that knowledge,” he says. “It is an eye, something that is itself perceiving.... When you’re there, it has visions.” But perhaps he was merely conducting certain Rauschenbergian experiments in dialogue; it is possible to catch him peeping slyly at his listeners when they think he is most in earnest.

s oblique as Turrell can be, after hanging around for a few days I did begin to get a sense of a metaphysic. He seems to have a vision of a world whose active components are not physical entities, things with weight, but spaces. To most of us, a visual act or event is a two-party affair, linking the observer with the observed. Turrell seems to believe that all the action happens in the space that separates the two. The space makes all the decisions; it controls what the observer gets to see and what the observed gets to show. Sometimes it seems that he sees spaces as conscious life forms; he talks of watching spaces watch themselves. “Roden Crater has knowledge in it, and it does something with that knowledge,” he says. “It is an eye, something that is itself perceiving.... When you’re there, it has visions.” But perhaps he was merely conducting certain Rauschenbergian experiments in dialogue; it is possible to catch him peeping slyly at his listeners when they think he is most in earnest.

After the sky had rolled the crater out on that first day of my visit, I turned, half dizzy, away from the ocean floating overhead, walked to the bottom of the bowl, lay down, and looked back at the rim. The wind had vanished; the air grew softer and warmer. Flies whined among the tumbleweeds. The walls of the crater had drawn into the sky, and the sky had descended to lie across them. The illusion of being sealed inside was so strong that my brain felt compelled to manufacture the sound, faint but unmistakable, of metal sliding over metal. Not fifteen feet overhead tiny clouds, like white flecks in fingernails, scrolled by. One would have thought that the volcano had just given them birth, and there they were, streaming off toward all corners of the globe, ready to take up the great work that lay ahead.

illions of years ago a vent tore open fifty miles beneath what is now central Arizona. Through this lesion the pressures of the deep interior took slow aim at the roof of that world, the floor of our own, and commenced a bombardment of molten rock that is continuing still. Over time this barrage, the remains of which are known as the San Francisco Volcanic Field, walked north and east, just nicking the edge of the Painted Desert, near what are now Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico. Right at the point where field and sands touch, a small, exceptionally well formed cinder cone can be seen, standing off from the other volcanoes, deeper into the desert. From a certain angle the cone has the shape of a bow wave, as though something alive were running under the sand, out toward the midst of the coral and orange landscape. This is Roden Crater.

he reasons visitors arrive, contribute, and go home with enthusiasm probably lie less in the view than in the reputation of the artist behind the project. Though only in his mid-forties, James Turrell is by any standard a major American artist. He has had retrospectives at the Whitney Museum of American Art, in New York, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, in Los Angeles, and he has shown at the Leo Castelli Gallery, in New York, one of the more prestigious private galleries in the world. He holds a MacArthur fellowship.

Both generations of psychologists found the technique difficult to control: their subjects couldn’t agree on what it was they were seeing. Apparently, the human retina refuses to believe in homogeneous fields. When exposed to one, it tolerates the phenomenon for a few moments and then begins casting about for other possibilities. Different retinas produce different theories. The most common report was of “swimming in a mist of light which becomes more condensed at an indefinite distance.” Most subjects described “sensing something vaguely surface-like in front of the face” some described a “cone-shaped three-dimensional surface,” a “cracked-ice effect,” a “web-like structure,” or rings of different sizes and shapes. There were reports of memory activation, time distortion, and other hallucinations. Sometimes observers felt that their eyes were in violent motion. When a homogeneous field was used as the ground against which an object was viewed, contours blurred and shapes transformed. Sometimes the objects seemed to vanish, leaving subjects uncertain as to whether their eyes were even open. After effects included extreme fatigue, great lightness of body, dizziness, and impaired motor coordination, sense of balance, and time perception. Sometimes subjects appeared intoxicated.

During that decade the art culture of the nation was, naturally, radicalized. One form this took was a systematic hostility to art as a commodity—as something that could be marketed, bought, auctioned off, or collected. Performance art and earthworks were part of this critique. A third and less well known part was “perceptual environments,” which set out to suggest that the perception of an object was less a function of the object itself than of the establishment-defined environment surrounding that object. This was the wing Turrell drifted into and the context in which he began to explore the special power of the homogeneous field. In particular, in 1968 Turrell, the Los Angeles artist Robert Irwin, and Ed Wortz, a physiological psychologist, entered into a celebrated collaboration to probe the possibilities of the fields.

There was nothing in these spaces but light, usually of a single shade. There was almost no sense of the artist’s hand, of a deliberate manipulation. The light in the chambers appeared alternately transparent and opaque. Some viewers experienced an illusion of solidity so pronounced that they tried to lean against the large chamber openings and fell through; three of them suffered such injuries to their bodies and egos that they filed suits against Turrell for maintaining a deliberate and dangerous deception. The critics were ecstatic. They declared the medium sensationally novel and the pieces utter knockouts, combining sensuousness with minimalist elegance. Many found them numinous, mystical, an invitation to meditate on the nature of the void. In particular, the critics embraced the very feature that had made the Ganzfeld seem so appropriate as a critique of the art experience - their power to destabilize perception, the delicious way in which they subverted the very idea of looking. Ross Wetzsteon, of the Village Voice, wrote,

As you watch, your sense of substance constantly shifts—the panel solid, then dematerialized, then solid once more . . . the panel floats in space, toward you, away from you, shimmering in place. You’re hypnotized, confused—what you experience contradicts what you “know,” and you begin to realize that James Turrell’s work is asking you to question the very nature of materiality.A “brilliant success,” said Robert Hughes, of Time.person thinking about homogeneous fields would naturally find himself reflecting on the greatest of these: the sky. Turrell, an enthusiastic pilot who spends as much time in the air as he can, had abundant opportunity for this sort of reflection, and in

the early seventies found himself focusing on the sky’s height. The illusion that the sky is a ceiling, which goes by the pretty name of celestial vaulting, is famously strong in children, and most of us, if asked to set aside what we know about the atmosphere, could come up with an altitude at which the ceiling appears to lie at any one moment. This figure is not stable. The apparent height of the sky is a function of the apparent distance of the horizon: specifically, the closer the horizon, the lower the ceiling. (It seems that our sense of the sky’s form stays the same regardless of the altitudes we are at.) Turrell’s first thought was of a big bowl in which people could walk up and down, the interior walls. As, viewers moved down the, sides of the bowl, the horizon, defined by the lip, would narrow and the sky would descend. What he found most intriguing about the idea, he says, was its power to demonstrate that people "control the shape of the space in which they move."

Roden fell short of perfection in only one respect: its dish was not circular but saddle–shaped. Otherwise, it had everything, including the advantage of being privately owned and therefore free of the public-lands bureaucracy, which Turrell thought might prove slow to appreciate his intensions. As it turned out, he had the same problem with the actual owner, a cattle rancher, who could not be persuaded of the benefit of having an art museum, or something, right in the center of his range. Turrell put him on hold for a bit and approached the Dia Art Foundation, which specialized in supporting large environmental pieces. Dia agreed to buy the crater, pay for reshaping the bowl, and take over responsibility for maintenance and visitor control once the project was finished. Turrell went back to the owner, who once again refused to sell.

urrell asserts that no one flying overhead will have any sense that construction has taken place. He intends to replant the bowl with the original vegetation, which will come as a shock to the tumbleweeds. The finished project will have none of the clues that identify works of art or art institutions: there will be no labels on the walls, no information booth, no recorded cassette lectures for rent. There will be no gift shop, restaurant, visitors’ register, or plastic box for contributions. No postcards will be sold. There will be no security guards, parking lot, landing strip, or escalators. In fact, if Turrell’s dream is perfectly realized, there will be no spectators, or hardly any: he thinks the largest number of visitors the project can handle will be around three a day.

s oblique as Turrell can be, after hanging around for a few days I did begin to get a sense of a metaphysic. He seems to have a vision of a world whose active components are not physical entities, things with weight, but spaces. To most of us, a visual act or event is a two-party affair, linking the observer with the observed. Turrell seems to believe that all the action happens in the space that separates the two. The space makes all the decisions; it controls what the observer gets to see and what the observed gets to show. Sometimes it seems that he sees spaces as conscious life forms; he talks of watching spaces watch themselves. “Roden Crater has knowledge in it, and it does something with that knowledge,” he says. “It is an eye, something that is itself perceiving.... When you’re there, it has visions.” But perhaps he was merely conducting certain Rauschenbergian experiments in dialogue; it is possible to catch him peeping slyly at his listeners when they think he is most in earnest.